Part protest, part commemoration, and part celebration, Pride Month joyfully invites us all to see the rich and diverse lives of queer folks — and to recognize that as far as we’ve come (at least here in the U.S.), we still have a long way to go to achieve a world in which LGBTQ+ people are fully seen, safe, loved, and liberated.1 Philanthropy has a role in achieving that goal, but it, too, has a long way to go in better supporting LGBTQ+ communities.

Right now, most funders don’t consider themselves to be LGBTQ+ focused funders. That might be because, according to the most recent tracking report from Funders for LGBTQ Issues, LGBTQ+ communities and issues are specifically targeted for only a small fraction of philanthropic giving. The reality, however, is that nearly every funder is building relationships with queer grantees and often supporting organizations led by LGBTQ+ people, whether they know it or not. And, for any funder that focuses on historically marginalized populations or has intentionally centered equity as a value in their grantmaking, the experiences of queer populations should be part of the conversation. Each aspect of our identities affects our experience, and often the challenges facing marginalized groups can compound one another.

So, every funder should be concerned that LGBTQ+ identified grant recipients have significantly less positive experiences with and perceptions of their funders than their straight peers do — at least as measured through response to CEP’s Grantee Perception Report (GPR) surveys.

Understanding these less positive grantee experiences requires visibility. However, individual funders might have only a handful of grantees who identify as LGBTQ+, which means it can be tricky or impossible to ask important questions about their experiences. These obstacles to recognition are also magnified because this is a group that can often feel pressured to make themselves invisible for all kinds of reasons — including because they may face uncomfortable dynamics with grantmakers who hold funding power but may be silent about their perspectives on queer rights.

That’s why, in CEP’s assessment work, it’s our standard practice to ask about identity and disaggregate data by demographics regardless of whether a funder is focused on direct funding to LGBTQ+ issues (or gender, race, or disability focused funding). As a result, we can look across CEP’s grantee dataset of over 50,000 grantee partners at nearly 350 funders, to reveal important patterns in the experience of LGBTQ+ identifying survey respondents that might not be visible for individual funders.

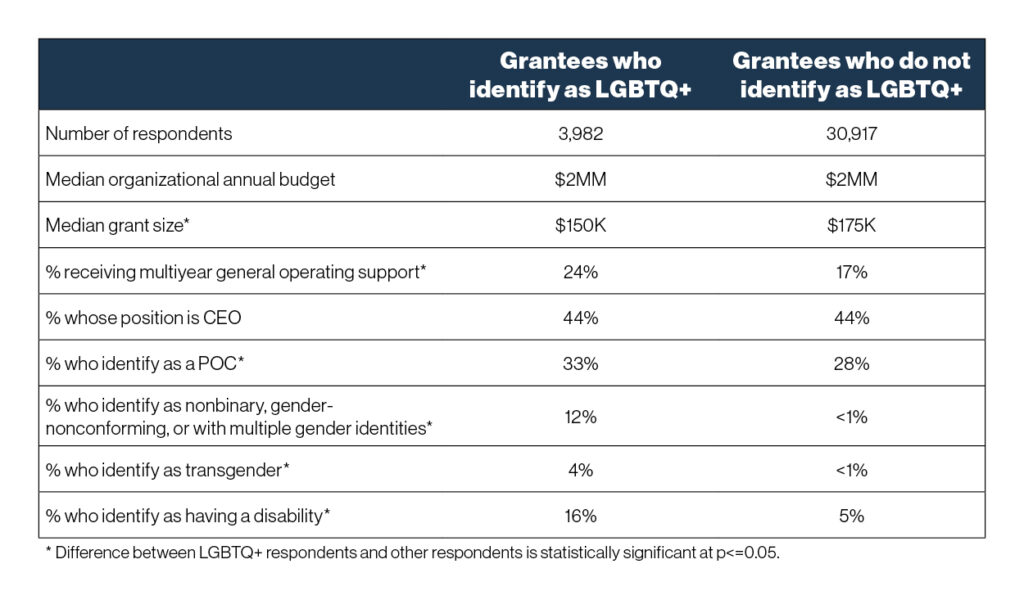

Let’s start with some of the basic numbers. In CEP’s grantee survey dataset, 11 percent of survey respondents identify as LGBTQ+. While LGBTQ+ respondents are equally represented in executive leadership positions in our dataset, they are more likely to have intersectional identities that are more marginalized. Specifically, LGBTQ+ respondents in CEP’s dataset are significantly more likely to identify as a person of color (POC) and as having a disability. They are also more likely to identify as nonbinary, gender-nonconforming, with multiple gender identities, and as transgender.

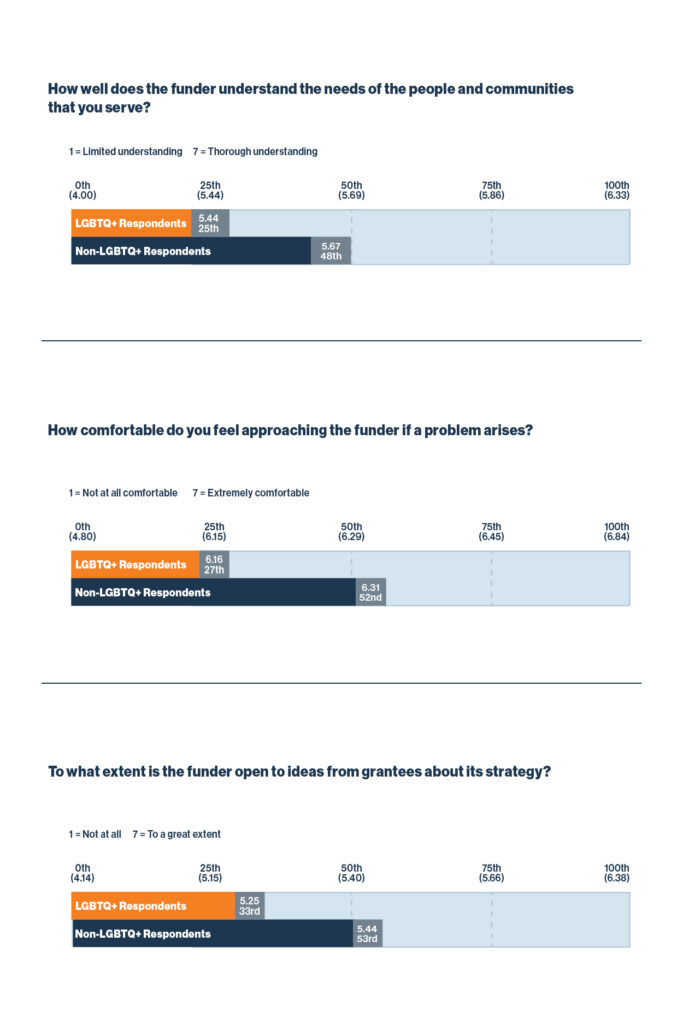

When we looked at differences in experiences based on whether grantee survey respondents identify as LGBTQ+, we see a consistent pattern of small differences, where respondents who identify as LGBTQ+ provide significantly lower ratings on most measures. Specifically, they rate significantly lower for their funders’ understanding of their organizations, fields, and the contexts in which they work. They also rate lower on nearly all measures related to relationships, and they find their funders’ administrative processes to be less helpful. This pattern reflects similar findings for grantees who identify as nonbinary and gender-nonconforming.

Calling these differences “small,” does not imply they’re not meaningful. Differences are often about 0.1-0.2 on a 1-7 scale, which represent fewer grantees having the most positive experiences and translate to a difference of a couple percentiles to up to 25 percentiles in our benchmarked dataset. And these differences are often much larger for individual funders.

Here are some examples of how these differences show up in our dataset:

We also see some other factors that are helpful to keep in mind when interpreting differences in experience. In particular, a significantly higher proportion of LGBTQ+ respondents indicate receiving multiyear general operating support (24 percent vs. 17 percent) — which, fieldwide, we tend to see associated with more positive experiences. This makes the differences in experiences among LGBTQ+ grantees all the more striking.

Because this pattern of small average differences is so consistent across themes in our survey, we think it’s important for all funders to pay close attention because it can help refine their approach to ensuring that all grantee partners have the kind of consistently positive experience that can maximize their — and funders’ — effectiveness. These average differences likely translate to meaningfully different experiences that could easily be missed if funders aren’t specifically asking themselves whether they see their LGBTQ+ grantees, understand their hopes, needs, and perspectives, and help their own staff consider how best to engage these grantees. In the words of one LGBTQ+ identified grantee:

“(My organization has) intentionally built a staff that reflects the people we serve — people from working class communities of color and immigrant communities, parents and family caregivers, queer, trans and nonbinary people… This means that the intersectional pressures faced by people in communities that face structural disadvantages are also faced by people on our staff. They need to take time off to care for family, to tend to their own health, to process attacks… So, as a result, we may have to shift our focus, we may take longer to implement programs, we may struggle with reporting and administrative requirements…. Patience, trust, and care from our philanthropic partners … will help ensure long term organizational sustainability.”

We recently worked with a funder that for the most part didn’t see itself as a targeted funder of LGBTQ+ issues. We shared with them that their LGBTQ+ grantees were having less positive experiences, which was generally not the case for this funder’s grantees with other types of historically marginalized identities. Their first hypothesis was that LGBTQ+ grantees would cluster in a certain region they were funding and would be the recipients of funding from one team that did directly address some LGBTQ+ issues. But the reality was different: LGBTQ+ grantees were spread relatively evenly across all of this funders’ work. And, in fact, for its team most directly focused on funding LGBTQ+ issues, this pattern of lower ratings from LGBTQ+ grantees did not exist. With that information, they could learn from what was working and could emphasize the importance of creating awareness of the needs and priorities of LGBTQ+ grantees across their teams and broadly at the organization.

So, as Pride Month comes to a close, it’s a moment for all funders to do the same: commit to implementing safe approaches that invite LGBTQ+ grantees to be visible, to understanding their needs, and to closing the gap in their experiences as grantees.

Kevin Bolduc is vice president, Assessment and Advisory Services, at CEP. Liz Kelley Sohn is a manager, Assessment and Advisory Services, at CEP.

- There is no single agreed upon term to encompass the diverse community of queer, LGBT+, gender-nonconforming, and trans people. We will primarily use the term LGBTQ+ in this blog post because it’s the term CEP uses in most of its demographic survey questions. ↩︎