The other week, I was presenting at a conference about the importance of nonprofits systematically eliciting perceptual feedback from clients, or those they seek to help, about how things are going from the clients’ own perspectives. This practice, often termed constituent or beneficiary feedback, is gaining momentum in the nonprofit and philanthropic sectors.

Indeed, a recent CEP publication, The Future of Foundation Philanthropy, highlights that foundation CEOs rate learning from those they are ultimately trying to help as one of the most promising practices to increase foundations’ impact in the coming decades. And a growing national funder collaborative, Fund for Shared Insight, continues to make investments to catalyze improved feedback efforts across the sector. As a result, more and more nonprofits are jumping aboard, creating ways to systematically listen to their constituents and act on what they hear.

Back to the conference — after my presentation, a man from a municipal human services agency described to me a large dataset that his organization is building about clients’ behavior and participation in various nonprofit programs. He was enthusiastic about the information collected on attendance and other measures of progress, and he was excited that it represented a great example of constituent feedback.

Unfortunately, this wasn’t what I had been talking about — but that’s not his fault. Rather, it was yet another reminder to me about the need in this field for an improved definition of what we mean when we say feedback.

Feedback is a multifaceted concept that embodies lots of different types of data and inputs. And because we as a field have not always had clear definitions about what we mean by feedback — and more specifically, perceptual feedback — we often talk at cross purposes.

Laura Jump noted the need for greater clarity of definitions in her 2013 landscape review of the constituent feedback field, writing, “The one clear message from the literature is that the terminology used in this field is not standardized, which leads to confusion of purpose, ideas, and hence conclusions.” More recently, Feedback Labs published a paper called Is Feedback Smart? that reviews select literature about the relationship between feedback and outcomes. Many readers weighed in on an open forum, but instead of commenting on the paper’s thesis or conclusions, a much more basic question emerged: “What exactly is perceptual feedback?”

Defining perceptual feedback

Fund for Shared Insight asked my consulting group to help answer this question. The result is the just-released Perceptual Feedback: What’s It All About?, a publication intended to offer a consistent and practical definition of the term.

“Simply put,” the new paper says, “perceptual feedback refers to the perspectives, feelings, and opinions individuals have about their experiences with an organization, product, or service that are used to inform and improve the practice and decision-making of that organization.”

Perceptual feedback captures sentiments of both the head and the heart, the paper goes on to explain, gathering information about what individuals did; whether an interaction met their personal standards; and how that interaction made them feel (e.g. supported, respected, or delighted).

To arrive at our definition, we break down perceptual feedback into its constituent parts, first defining “perceptions” and then “feedback,” with a focus on teasing out how feedback differs from other types of information. We note that while it is easy to think of feedback as equivalent to input, it is inherently distinct, as feedback implies a commitment to some sort of response. Management theorist Arkalgud Ramaprasad terms this the “purposive character of feedback.” In this way, perceptual feedback provides insights about a gap in experience versus expectations and, in turn, informs decision-making,

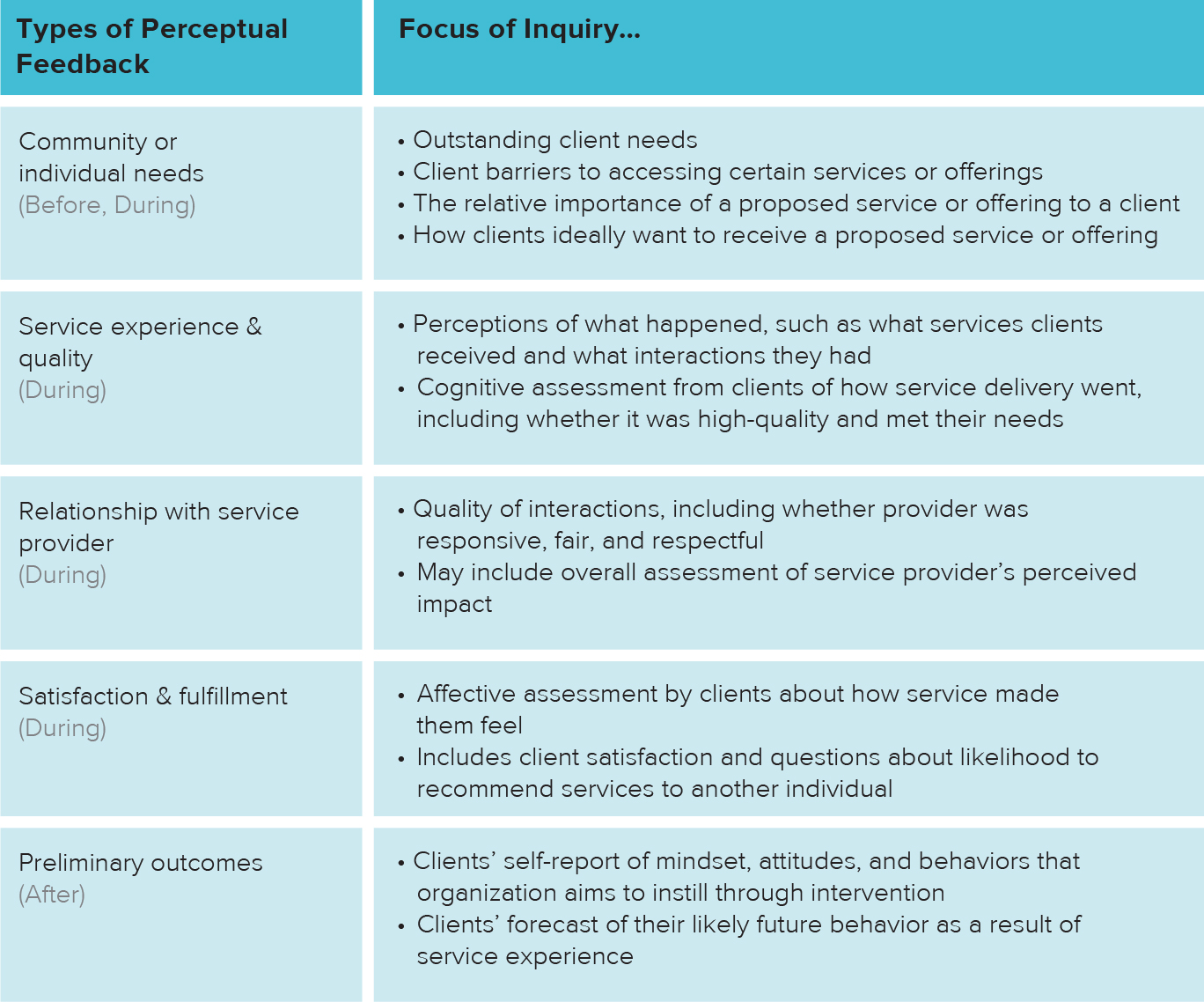

Our paper also introduces a typology for looking at the range of perceptual feedback that can be provided by clients, which we hope will be useful for organizations as they design and plan data-collection activities.

By including this taxonomy or typology, we hope that organizations can begin to think more systematically about the range of feedback that they can elicit from clients; why they ask the questions that they do; where feedback would be most beneficial; and how they can improve their feedback practices. Our taxonomy also reinforces a key part of the definition of perceptual feedback: that, since it is based on client experience, it should be gathered primarily during the implementation of a program or service, as opposed to before or after.

Our hopes for the future

As the paper states, “We have seen the power that perceptual data can have in challenging assumptions, bringing forward client voice, and helping to improve service provision. When implemented well, perceptual feedback practices and systems can generate powerful complementary performance data and tangible insights that can dramatically improve service delivery and guide organizational focus.”

Our hope is that clearer definitions and a more consistent understanding of what we mean by perceptual feedback will lead to better conversations, implementations, and outcomes. Personally, I look forward to meeting up in the future with my dataset friend from the conference and hearing how his organization now also collects perceptual feedback — in addition to program outputs or outcomes — in pursuit of improving its programs and services.

In the spirit, we welcome feedback on the concepts we put forth in the paper, and we hope we can all move together towards the goal of best serving the people we collectively aim to help.

Valerie Threlfall is an independent consultant focused on strategy development and performance measurement design for nonprofit organizations, and the project lead for the Listen for Good initiative of Fund for Shared Insight. She was founding director of CEP’s YouthTruth initiative. Follow her on Twitter at @valthrelfall.