There is one word that stuck with me across all of the sessions I attended at CEP’s Stronger Philanthropy conference last month, and which hitched a ride home with me as a whisper in my ear that has been present every day since.

That word? Listen.

Law and religion scholar John Inazu spoke about philanthropy’s role in moving beyond political divisions, and Better Angels shared how they bring individuals of different political parties together to bridge partisan divides. Matthew Desmond, author of Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City, shared the stories of eight families he followed for a year who struggled daily to keep a roof over their heads for themselves and their children — followed by the accounts of two panelists, Luis Caguana and Tecara Ayler (both affiliated with Inquilinxs Unidxs por Justicia), about their experiences with poor housing conditions and eviction and how they are contributing their voices to advocacy and organizing to fight unfair housing policies. Finally, CEP President Phil Buchanan closed the conference with a call to philanthropy to be at its best in this time of increasing divides and divisiveness. And, as always with CEP, there was more.

What I heard loudest, across it all? Listen.

What whispers to me now as I sit at my desk at the Communities Foundation of Texas office in Dallas and consider our next year of capacity-building training for nonprofits; attend internal diversity, race, equity, and inclusion sessions; have breakfast with nonprofit leaders sharing their challenges; and find myself puzzling over what the heck happened between me and another employee that landed us on two different pages is…. Listen.

The first thing I think of when I think of CEP is data. And exceptionally good data at that. As a former survey researcher trained up within RAND’s Survey Research Group, my relationship with data is like that of an oenophile to wine; not just any data will do. The source of the data, the way the data are collected, the integrity with which the data are handled and processed, and the way they are combined through statistical analysis into a final product all matter greatly to me. CEP staff, from very early on, earned my respect as fellow data geeks in the trenches of data collection and analysis.

But if you aren’t a data geek like me, that last paragraph is, well, boring! There is nothing personal or human-sounding about it. There are no words that indicate what is at the root of the practice of survey research, which in actuality is born of caring enough to ask another human about their personal experience in order to learn more and potentially change something based on it. You capture a sliver of their story through the process, and that is inherently personal.

What struck me as a frying-pan-to-the-head moment at the conference this year was that, at the heart of it all, what CEP is doing — through their survey assessments and through the curated agenda and speaker lineup at the conference — is elevating the importance of really listening, and then listening some more.

And we’re not talking here about the kind of listening-but-not-really-hearing that we do most of the time. The power of true listening begins with being present and open to another person’s perspectives and realities, continues with a curiosity toward another’s views on reality that allows you to go deeper with them and better understand via their own personal window on the world, and often ends with takeaways and learnings that change the insights and trajectories that you as an individual may not have come up with on your own.

We use all kinds of jargon in philanthropy that is meant to ensure listening to a number of perspectives is a part of our foundations’ best practices: “amplifying lived experience;” “incorporating community voice;” “elevating diversity of thought;” “cultivating an open exchange of ideas to ultimately ensure better outcomes;” “using feedback to inform our work.” Yet what strikes me about all of these phrases is how distant the language is from what is at the heart of listening, which is allowing ourselves and our actions to be touched and changed by the perspectives of others.

What impressed me at this year’s CEP Conference was the emphasis on the importance of the listening process itself in our field. We need to find more ways and spaces to listen, repeat back what we hear, and then listen some more. We need to allow ourselves to be more relational and less clinical, as well as more open to the potential faultiness of our own ears and eyes when we try to interpret what we hear and see without checking in with others about our inferences. It may be 2019, but we humans are still notoriously bad at reading others’ minds without importing our own experiences and beliefs into our guesses about what others are thinking and feeling.

In my experience, exceptional philanthropy isn’t ivory tower work. It is most often relationally based, messy in the middle, and hard. Social change is, of course, always hard stuff. But listening-based philanthropy requires us to be vulnerable. It requires extra work to ensure others’ opinions and wisdom are poured into the collective pool of knowledge, and it insists that we be willing to overwrite our own conclusions as new information comes in. It requires us to ask for feedback regarding when we as foundations and people have it wrong vs. right, and it requires us to be willing to change our approach, even when it’s uncomfortable or inconvenient. And it asks us as “thought leaders” to please, pretty please, not lead with our own thoughts in the absence of rich, full-bodied perspectives from others.

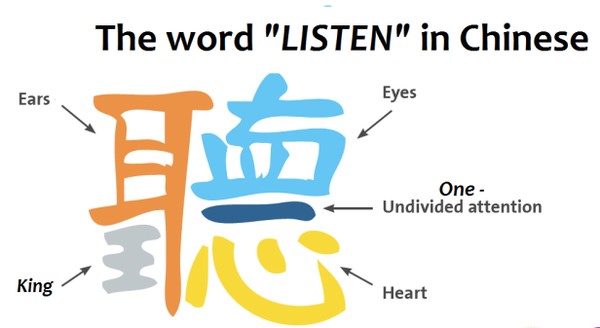

I would love to better practice the full-bodied meaning of the word listen that is built into the Chinese character for the word:

The character calls us to utilize all of our senses (ears, eyes, heart) when listening, and to provide the person to whom we are listening with the undivided attention and respect we would afford a king. How would it change our work in philanthropy if we analyzed our data with this in mind? How would it change the conversations we have with grantees and members of the community? How would it affect our takeaways from these interactions?

I’m anxious to find out. Join me. Practice makes proficient.

Sarah Cotton Nelson is chief philanthropy officer for the Communities Foundation of Texas. Follow her on Twitter at @Philanthrofeme.