CEP’s report on nonprofit diversity efforts comes at a time when we at the Ford Foundation have been thinking critically about how we collect, analyze, and act upon diversity data from grantee organizations.

As a funder, we know we can play a role in normalizing diversity data collection and initiating conversations about diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in the fields in which we work. And we know we have the potential to cause harm if we raise those topics in an unclear or ineffective way. For example, we have long collected diversity data from organizations that are applying for funding. But we haven’t always been clear on why we collect it and how it should be used. This lack of clarity led to a lot of counting and box-ticking, but not to meaningful conversations or changes in practice — both internally and with the organizations we support.

Over the last year, we decided to revise our entire proposal process, including questions about DEI. In doing so, we reexamined our intentions and our own DEI goals. This process is ongoing, but we wanted to share a bit about where we’ve landed for now — and seek your feedback on how we can do better.

What we’ve done in the past

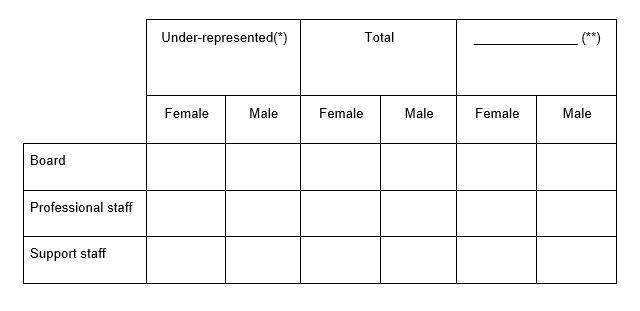

Our previous method of collecting organizational diversity data from grant applicants was through a “diversity table” embedded in a Word document that looked like this:

Though we used this table for many years, two key issues arose:

1. The data we collected was insufficient for understanding an organization’s approach to DEI.

This collection method allowed organizations to define what “under-represented” meant in their context. As a foundation doing work around the globe, this gave us the flexibility to accommodate multiple forms of diversity that vary by region, such as religion or tribe. It also allowed us to explore the intersection of gender with other demographic identities. By keeping it so flexible, however, we questioned whether or not we were inadvertently watering down the meaning of diversity, and in doing so limiting our ability to conduct meaningful analysis across so many different categories.

One thing that definitely impeded analysis, though, was the mechanics of how we collected this data: it was trapped in Word documents in our grants database. As a result, we couldn’t easily track how an organization’s diversity was changing over time, and we couldn’t identify trends across the fields in which we work to understand what gaps existed and how we might address them. This begged the question: why were we collecting this data in the first place?

2. How this data was used was dependent on program officer competence and skill at talking about and supporting DEI.

Diversity data will only tell you so much about an organization’s commitment and approach to DEI; a conversation beyond the data is essential to building a true understanding. But we found that those conversations weren’t necessarily taking place. We were collecting the data and doing nothing with it.

In Nonprofit Diversity Efforts, 42 percent of nonprofit CEOs disclose that funders have not discussed diversity issues with them. While Ford program staff see the critical importance of DEI to our work in general, DEI conversations between funders and prospective grantees can be challenging to have. They require prioritization, effort, and training.

We learned there were several things standing in the way of our ability to have meaningful conversations. First, there’s the power dynamics factor. It’s hard to have an honest conversation about DEI goals and challenges during the proposal process when an organization may feel pressure to do or say anything to impress. Second, we know we have our own learning and work to do on the DEI front, so there were fears of looking hypocritical or judgy. Third, we had not articulated benchmarks about what “good” or “sufficient” diversity looks like, or had clarity about what our policy is when an organization does not exhibit diversity. Are we to use the carrot or the stick? So much of that had been left to program officers to navigate on their own.

These issues forced us to reconsider why we wanted to collect this data and how we were going to use it. We knew that grantee diversity mattered for our mission, but we’d lost the plot on how to identify and support it through our grantmaking. It was time for a change.

What we’re doing now

Moving to a new grantmaking system, Fluxx, gave us the opportunity to rethink our diversity questions as we overhauled and redesigned our entire grantmaking process.

Our first step was defining the value of collecting organizational diversity data. We articulated that we do this because it tells us:

- where organizations are in their commitment to diversity, which gives a point of comparison for ongoing conversation about DEI goals;

- what the aggregate trends are in the fields we support; and

- where our own blind spots exist, and whether our grantmaking and decision-making process excludes certain organizations or people.

And by moving to Fluxx, we could now collect this data in a structured data field (rather than embedded in a Word document!) so we could easily analyze it.

Having confirmed why we wanted to collect the data, we now needed to determine what data we would collect. We defined two key prerequisites to guide us:

- We only want to collect data on identities that we currently track within the foundation. If we haven’t figured out how to track it ourselves, we cannot expect organizations with less capacity and fewer resources than us to provide it.

- We do not want to collect data that puts any of the organizations or individuals we work with at risk. We want to be cognizant of the legal and safety barriers that may prevent organizations from collecting and disclosing this data. This is particularly true outside the U.S.

We then consulted with the Foundation Center, GuideStar, and D5 Coalition on their recommended categories. We landed, imperfectly, on collecting the following data from organizations during the proposal process:

- The total number (%) of women on the board and on the executive leadership team

- For U.S. based organizations, the number of board and executive leadership team members who are:

- Multiracial or Multi-Ethnic

- Arab or Arab American

- Asian or Asian American

- Black or African American

- Latin American

- Native American, American Indian, or Alaska Native

- Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander

- White

- Other

- Unknown or decline to state

The process of landing on these identities led to a lot of debate within the foundation. For example, why do we not collect data on LGBT people, people with disabilities, young people, or the myriad other identities a person can have? Folks were very aware of the signaling power we have as a large funder. Would we be unintentionally conveying a preference or favoritism by including some categories and not others? Were we missing an opportunity to normalize the collection of less frequently gathered data?

These were excellent and necessary questions. The short answer is: we strictly abide by our prerequisites — if we haven’t figured out how to collect it ourselves, we won’t ask others to provide it. We are in the midst of an internal DEI audit, which includes asking staff to self-identify their race, gender, sexual orientation, and disability status. As we get further along in our internal data collection process, we will likely refine the data we collect from organizations seeking funding.

Recognizing that our data collection efforts are imperfect, we knew we needed to provide additional space for exploring an organization’s commitment to DEI. So we added the following two questions to our applications, which we also follow up on in the reporting process:

- What efforts do you currently take to promote DEI within your organization, particularly for your board and staff? How do you proactively consider such factors as, for example, gender, race/ethnicity, and religious affiliation? Please also note any other under-represented groups you prioritize, and how. The Ford Foundation has begun a significant effort to deepen its own work on disability inclusion and raise the visibility about the need for more focused disability inclusion efforts in the philanthropic and NGO sectors. What efforts do you currently take to advance the inclusion of people with disabilities in your policies, staffing, and board?

- Please describe what goals, if any, your organization has developed around DEI? How do you track progress against these goals?

(We know that first question is way too long! But in writing it, every single word felt so important, particularly given our current focus on disability inclusion. Suggestions on how to improve the wording are most welcome!)

Beyond the grant application, we also recognize that we need to provide support to program staff on how to have helpful, constructive conversations about DEI with grantees and applicants. The 2007 GrantCraft guide, “Grantmaking with a Racial Equity Lens,” developed by the Philanthropic Initiative for Racial Equity, featured our diversity questions at the time as one of three examples of how foundations engage grantees on diversity. Looking back at the guide, the Ford Foundation example includes a “menu of support strategies.” We’ve each been at the foundation for at least three years, but this was news to both of us! Clearly, we all needed to get back in the habit of doing more than just collecting that data. And so, we’re starting on that path as of this year.

What we’re learning to date

So far, what we’re hearing from program staff are a lot of questions. This is a good thing — it means they’re engaging with the data and thinking about how to use it in service of stronger relationships with grantee partners. We hear (and are ourselves asking) questions like, “Are we doing enough on diversity ourselves as a foundation to justify asking these questions, or are we being hypocritical? Would we ever hold up a grant over lack of progress in this area? How do we adapt U.S. diversity terms for our global offices and grantees?”

In response, we’re working with consultant Inca Mohamed to build staff competence on DEI topics. This is not a one-time thing that a training could “take care of.” Rather, it’s about understanding the quality of the relationship between program officers and grantees. As CEP research has documented, this is a key determinant of grantee satisfaction. And in response to our most recent Grantee Perception Report (GPR) results, we’ve made improving the quality of grantee relationships a key internal priority for 2018.

This bodes well for our work on using diversity data more effectively, since two key success factors for diversity efforts are leadership buy-in and an institutional commitment to progress over time. This particular diversity effort is one of several we’re undertaking, including our internal DEI audit. We agree with the question, “Aren’t you being hypocritical if you don’t pay attention to your own diversity?” We’ve done some things, and are continuing to learn and do more. After all, that’s what we’d ask grantee partners to do in advancing their own diversity goals.

What we hope for the future

The recently launched GEO Culture Resource Guide describes how a strong culture within a foundation is essential to being effective. Our conversations around diversity data collection have coincided with our own internal work on DEI, and so CEP’s report comes at an opportune time. We are committed to learning and getting better about DEI over time, particularly when it informs our relationships with grantees.

We’d love to learn from you. Funders, what have you learned from gathering demographic diversity data? Nonprofit organizations, are there meaningful exchanges you have had with funders about diversity data?

Megan Morrison is an officer on the strategy and learning team at the Ford Foundation. Chris Cardona is program officer for philanthropy at the Ford Foundation. He can be found on Twitter @chriscardona.