“I get that listening is important, but what role am I actually supposed to play to make it happen?” A program officer from a large private foundation recently asked my colleague this question. The fact that this program officer wanted to play a role in listening to the communities at the heart of their grantmaking represents a definite shift in the field — 10 years ago I regularly heard grantmaking staff question why they needed to listen to communities at all.

Now, their questions are focused on how to listen well, and the specific ‘hows’ that program officers in particular ask about are many and varied: How do I have ongoing conversations with my grantees about how they want to listen? How do I listen directly to communities without my partners feeling like I’m checking up on them? How do I deal with hearing conflicting suggestions from different community members? How do I make the time?

It reminds me of the “Barbie” movie (bear with me). Once Barbie accepts that her existence didn’t solve “all problems of feminism and equal rights” in the real world, she faces all kinds of practical questions. Granted, most grantmakers don’t need to figure out how to quell an insurrection of Ken dolls. But they do need to figure out how, practically, to make room for listening when it feels important but rarely like their most pressing priority.

Over the course of the next month, the funders that make up the Feedback Incentives Learning Group will offer practical suggestions for how grantmaking staff can listen better, within the realities of their day-to-day work. We’re excited to widen the lens of what we mean by listening and offer actionable suggestions for how to do it well.

Two years ago, in our first blog series with CEP, we wrote about how funders are using their power to dismantle the incentive structure that rewards nonprofits for aligning with funder priorities rather than the needs and desires of the people most affected by their work. We shared that, as part of that work, funders are increasingly providing capacity-building support to help their grantees listen and respond to the people at the heart of their work: 36 percent of foundations we surveyed offered grantees funding, training, or other listening-related capacity support, and 60 percent of the foundations that didn’t were considering doing so.

It’s heartening to see, two years on, that funders are finding more ways to start conversations with grantees about how they want to listen to communities, whether by adding questions to grant applications or using grantees’ How We Listen reflections on Candid, and offering support, like sponsoring trainings or access to listening tools, to help them realize those aspirations.

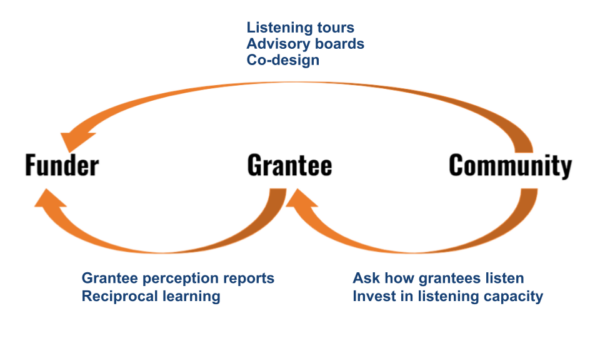

But much like Barbie Land needs many different Barbies to function, the ways in which funders hear community voices shouldn’t begin and end with just supporting their grantees to listen better. Funders should absolutely support grantees to listen well. They should also listen to their grantees, whether through the Grantee Perception Report, grantee convenings, or ongoing conversations. And they should also listen directly to the communities most affected by their grantmaking. Just as President Barbie needs the help of other Barbies to protect the democracy of Barbie Land, each of these three types of funder listening supports the others. They use different methods, make sense at different points in the grantmaking cycle, and uncover different, complementary insights.

Take REDF, for example, a grantmaker that invests in building an economy that works for everyone. REDF sponsored some of its grantees to participate in Listen4Good, a feedback capacity-building program, and made new funding available so those grantees could respond to the feedback they were hearing. REDF also incorporated some of Listen4Good’s feedback questions into a multi-year study of their job-preparation interventions so they could directly hear the hopes and dreams of participants in the programs they were supporting. And they sent grantees art supplies so they could make posters to share their visions for the future. “[Listening is] a powerful act to make things better,” says Yon Jimenez-Macuso, manager for learning and evidence at REDF. “By listening to our grantees, amplifying their voices and those of the people they serve, and continuously learning from them and their communities, we gather valuable insights that not only shape our work but also build real connections and drive meaningful change.”

We don’t expect every grantmaker to become an expert in all three types of listening overnight. Most grantmakers have specific areas of work where it feels easiest or most relevant to start deepening their listening practice. That’s why over the last year the funders that Feedback Labs works with have developed a tool that lays out different opportunities for foundations to incorporate high-quality listening. As we’ve workshopped the tool with other grantmakers, we’ve emphasized that it’s not about choosing one of these areas to invest in and sticking to it. Rather, the key is to identify the opportunity for listening that feels most relevant and feasible in your work now, and build to the other areas from there.

Five opportunities for listening

- Moving into a new issue area or community: As you start making grants in a new issue area or community, you’ll probably be figuring out who is already working in the system and determining what role you should play in the space. Useful listening approaches include listening tours, convening community members to create strategies for change, or one-on-one conversations with leaders in that area.

- Investing in grantees’ listening efforts: Many grantees are eager to listen, but lack the capacity, space, or time. Others are listening, but perhaps not in ways that are obvious or appreciated. Understanding how your partners currently listen to communities and what support they need to listen better can help you better direct support to grantees and partners. You can use grantee reflections on the How We Listen section of their Candid profile to spark conversations about their listening practices, and provide capacity-building support for grantees to strengthen their listening practices in the ways they identify.

- Strengthening internal processes, governance, and staffing: Listening to grantees and communities can help you improve your grantmaking processes and internal structures. You might be looking for ways to streamline grant approval processes, help staff get proximate to the communities most affected by your grantmaking, or recruit more board members, staff, and consultants with lived experience of the issues you’re trying to address through your grantmaking. Useful approaches include grantee survey tools like the Grantee Perception Report, staffing community liaison roles or setting targets for how much time staff spend in communities, and incorporating lived experience as a criterion when hiring consultants or recruiting new staff or board members.

- Evaluation and learning: Listening can help you evaluate your progress, sense changes in the systems you’re trying to influence, and adjust your grantmaking accordingly. Useful approaches include convening community members to identify signals of progress, listening to partners and community members as part of evaluations, and sharing what you’re learning with the people at the heart of your work and inviting them to help you decide what it means.

- Sharing power over grantmaking decisions: Shifting power over your grantmaking decisions involves deciding how participatory you aspire for your grantmaking to be, and identifying who is most affected by your grantmaking decisions and what decision-making power you can share with them. Useful listening approaches include advisory boards of people most affected by your grantmaking, engaging community members in grant program design, or adopting other participatory grantmaking tools.

Over the course of this blog series, different funders will share their experiences with these different opportunities for funder listening, and offer practical advice for how grantmaking staff, and program officers in particular, can approach them. We hope to offer tips that help you start building on the opportunities for listening that are in front of you. That is, after all, Kenough.

Megan Campbell is the senior director of Programs and Strategy at Feedback Labs. Find her on LinkedIn or join her at the 2024 Feedback Summit in Denver May 15-17.