Mackenzie Scott’s gifts now total over $14 billion to more than 1600 organizations. CEP’s ongoing “Big Gifts” study is documenting the significant impact these gifts are having on the leadership, values and work of the recipients. Given the scale of giving, the widespread impact, and the distinctive way Scott and her advisors made the gifts, we should also consider the potential effects on the social sector overall.

The social sector is too often overlooked as an essential part of U.S. society. To meet the needs of the people, American society requires its three sectors — business, governmental, and social — to be effective and balanced. The social sector needs strengthening to fulfill its vital roles alongside the economic and governmental sectors. Scott’s gifts offer the social sector, including philanthropy, an impetus to strengthen itself at a crucial stage of American history. But the sector itself must take advantage of the opportunity.

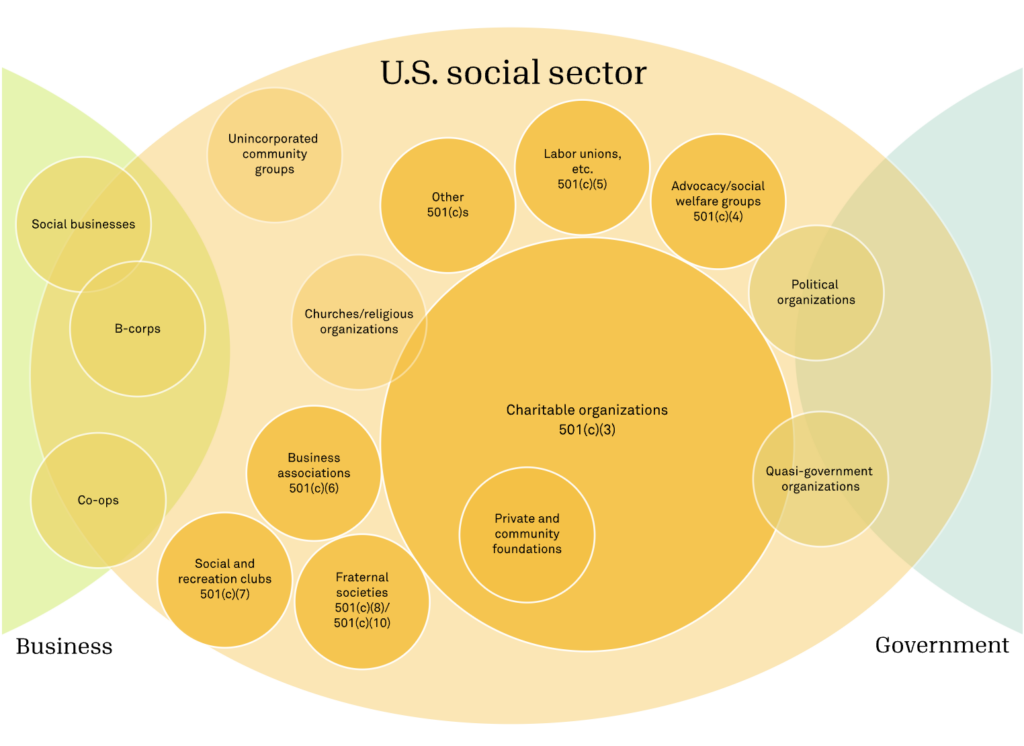

Graphic by Candid. Find it here.

What will that take? Fundamentally, we need to work towards a widespread public understanding of the U.S. social sector as a crucial part of society. Necessary steps include developing a shared language to talk about the social sector and promoting a basic grasp of the sector’s distinctive roles. Further, we need more systematic attention to the way the three sectors interact, including the risks from business and public sector incursions into the social sector.

What to call the sector?

Settling on what to call the sector and working to foster consistency in establishing the sector’s identity in public understanding may be one of our biggest challenges.

The first two sectors, which include much of what dominates common discourse, media attention, and extensive scholarship, are easily recognized and understood. The third sector is more elusive and suffers from the absence of an agreed upon name, even by scholars studying it. Variously, it is referred to as the independent sector, the nonprofit sector, the third sector, the non-governmental sector, civil society, the voluntary sector, the plural sector, and the social sector. Several of these are puzzling to the public or misleading. An ideal term would accommodate multiple views and garner widespread use and recognition, analogous to how “community” is widely used by the public.

I’ve used “social sector” as the preferred option in this post. It avoids weaknesses in other terms and is consistent with the sector’s many functions. What’s more, it is already in widespread use, including by Candid, which released its U.S. Social Sector Dashboard in 2021, as well as by Mackenzie Scott.

How do we define the sector’s role?

The other two sectors have well understood roles. The business of business is to make a profit, as Milton Friedman famously noted. And the governmental role, while deeply contentious at the boundaries, is anchored in the founding documents, the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. The social sector has multiple roles and a range of organizational types, not easily summarized or reduced in an overarching description.

It may be helpful to highlight a few examples of how the sector is viewed, beginning with a recent description of its multiple roles:

- Reaching out and doing service for the most vulnerable in society

- Ensuring human development and democratizing power

- Innovating and experimenting to find solutions to social problems

- Speaking out against injustice or oppression

- Providing avenues for people to contribute to their communities

- Upholding values through actions that elevate society.

Almost 30 years ago, management scholar Peter Drucker viewed the social sector as the solution to the emergence of the knowledge society, which in his formulation was eroding the social ties that took care of “social tasks.” His view was, “The task of social-sector organizations is to create human health and well-being,” with a second, and equally important purpose of creating citizenship. Drucker concluded, “The emergence of a strong, independent, capable social sector — neither public sector nor private sector — is thus a central need of the society…”

It’s clear even from these few examples, the overall role of the social sector is complex. But it is equally clear that the sector is central to our society. The strength of the sector lies in its multiple roles, its complexity. It serves as a public commons that empowers different views, promotes altruism, encourages personal interaction and seeds collective exploration. Collectively, it is a community of communities.

What can the sector, and philanthropy in particular, learn and do based on Scott’s gifts to date?

Let’s begin with re-examining what we mean when we say Scott’s gifts. She is quite intentional in describing what she is doing as giving, not philanthropy. And she is clear that her idea of giving includes all manner of helping others with whatever resources — time, money, labor, ideas — each of us happens to have. We overlook a valuable gift if we focus only on the wealth she is sharing. Scott’s periodic Medium posts are a vital part of her giving. In them she imparts her rationale for giving, her focus on equity, her approach and criteria for selecting recipients, her philosophy for giving in a democratic society, her belief in a diversity of voices, and her reasons for relying on what she calls ‘funds.’

In her November Medium post announcing the almost $2 billion in gifts to 343 organizations she says,

“Of special note is that many of the organizations are funds. For anyone similarly interested in supporting leadership of people from the communities they’re assisting, funds are a great resource. They pool donations and spread them across a diverse group of smaller organizations working toward a common cause.”

Her affirmation of the values and practices of these funds, as well as her own humility raises a question for any giver, institutional or individual, about trust: Can an existing fund — a United Way or a Community Foundation or a Women’s Fund, etc. — allocate resources more effectively because of their knowledge and experience in their communities?

Philanthropies (and givers of all sorts) will differ with Scott’s approach due to their varied circumstances — aims, values, history, decision-making structure, and community context. But they could discuss their own practices, relationships, and values in light of Scott’s approach as an exercise in self-reflection. The comparison would be constructive, sharpening everyone’s thinking.

Scott’s gifts are a catalyst to think and act collectively, to affirm the sector’s value, to assure its vitality, and to fight and protect it from incursions and harm from the business and governmental sectors. Her gifts encourage us to apply a decade of collective impact experience with communities to the social sector overall. This could include, for example, more joint efforts by philanthropy-serving organizations and social sector leadership entities.

It is too soon to assess how Scott may ultimately influence the social sector; there is much giving to do before she “empties the safe.” Last month she unveiled her new website, containing a searchable database of recipients along with all her essays. The design and content of the website reinforces her perspective on relationships with the sector — open, encouraging, respectful. The site also signaled plans for a big shift in how she gives, to theme-based, open calls for proposals evaluated by experienced teams aligned with those themes. There will be much to learn as she adopts practices similar to those widely used in organized philanthropy, including how her values are incorporated into this approach. The planned process also presents an opportunity to accelerate sector-wide learning by fostering stronger networks around the proposed themes.

Whether this shift in giving will enhance or impede the overall sector impact of her gifts remains an open question. But already Scott’s gifts have opened the door to broader social sector developments that will benefit our society for years to come.

Bob Hughes is former vice president and chief learning officer at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and, most recently, was president and CEO of the Missouri Foundation for Health. He lives in Providence, Rhode Island. Find him on LinkedIn.