At the Gates Foundation Greater Giving Summit last spring, there was a hearty discussion about how we leaders in philanthropy should approach our work with a stronger equity lens. The conversation highlighted how methods used to pursue greater impact in recent decades have either reduced or not improved equity. The data shows that black-founded nonprofits, for instance, are still much less likely to receive funding, all things equal. Trust-based philanthropy, the essential role of proximate leaders, collaborative philanthropy, and other concepts were discussed as ways to foster equity.

This is reflective of the broader discussion in the philanthropic industry: the tension between the “effective giving” paradigm of the last few decades and the emerging “equity” paradigm most prominently represented by trust-based philanthropy.

Here, I’d like to explore the tension between the effectiveness and equity paradigms and highlight forthcoming new tools that we at Charityvest believe will foster the integration of the best parts of both through a new model I’m calling, “philanthropic agency.”

Deconstructing What is Happening in Philanthropy Right Now

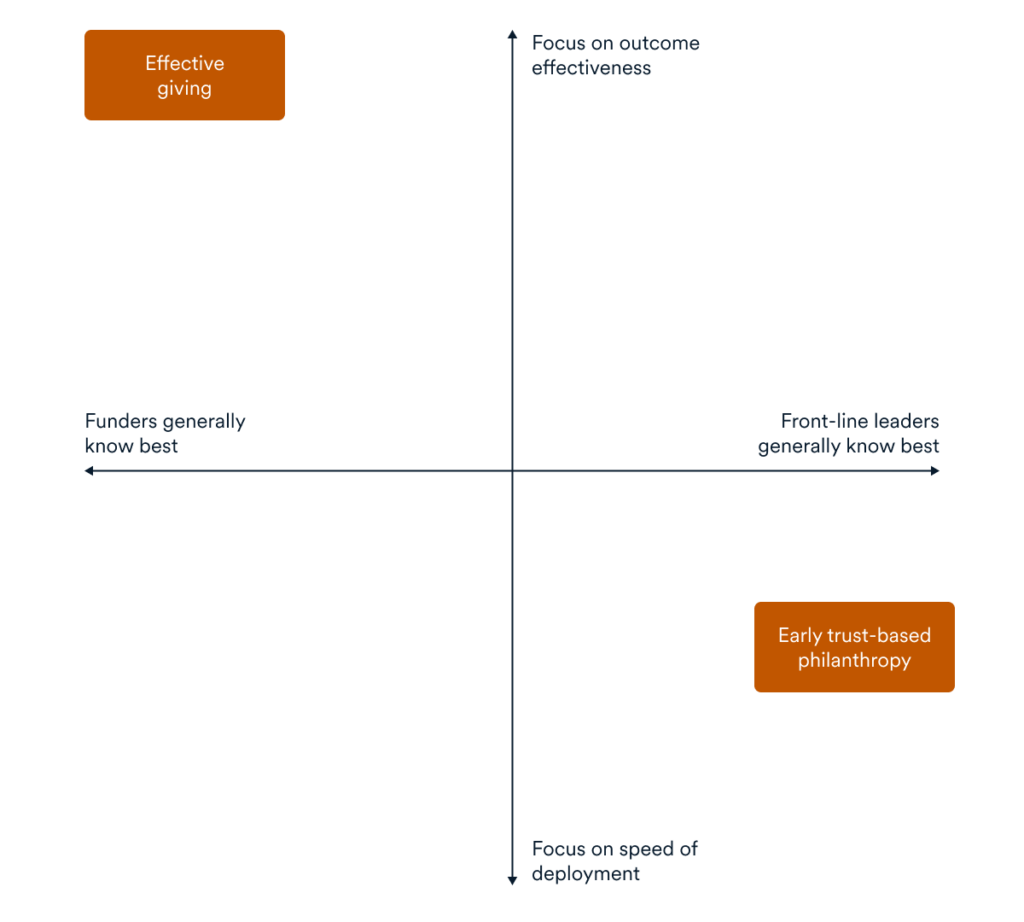

“Effective giving” has been dominant over the last 20 or so years, characterized by an emphasis on monitoring, evaluation, restricted grantmaking, and other top-down nonprofit management tactics. Trust-based philanthropy starts with a sweeping critique against the assumption that grantmakers “know best” and can coax nonprofit leaders toward greater impact through measurement and milestones. In contrast to effective giving, it calls for trust in nonprofit leaders as those who know best, putting resources in their hands boldly and quickly without strings or hoops.

Putting these two industry trends into a visual on their basic assumptions, effective giving moved funders into the top left of this chart, and trust-based philanthropy is currently moving many to the bottom right.

The Potential Pitfalls of Trust-Based Philanthropy

I’ve heard several nonprofit leaders speak ironically about a problem popping up regarding trust-based philanthropy: equity. Some forms of trust-based philanthropy, à la Mackenzie Scott, where grantees are picked in a not-very-transparent process can leave nonprofit leaders confused as to who is getting funding from grantmakers, when, and why.

At the Gates Greater Giving Summit, many proximate leaders who spoke applauded the shift in focus away from burdening nonprofit leaders with funding hoops, but they also mentioned how they felt like funders were not seeking to deeply understand and learn what’s important to their organizations, and therefore weren’t seeing the same impact opportunities on the same timelines. The potential dark side of trust-based philanthropy is a pullback from seeking understanding, proximity, and relationship.

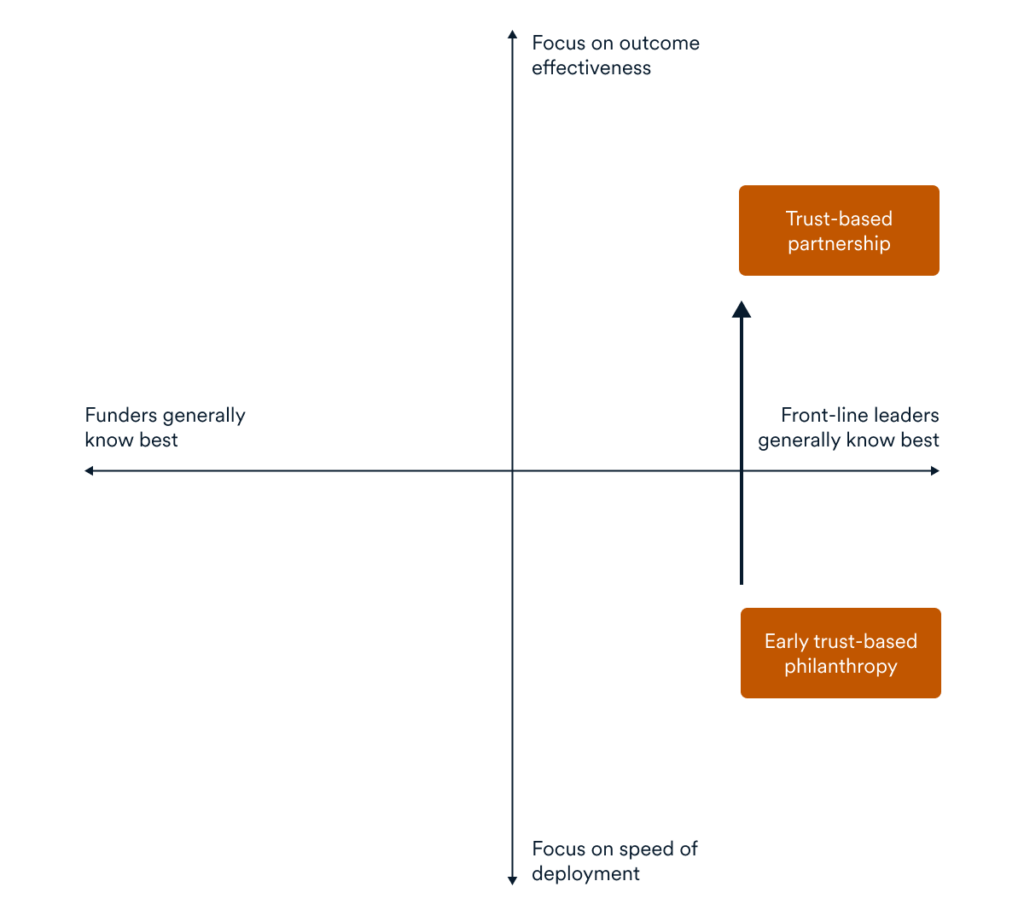

What nonprofit leaders want is a trust-based partnership. They want to know their financial partners understand the essentials of the complexity they face in creating impact, so resources can dynamically flow to what’s effective in line with opportunities. They want resources now, but they also want to feel they have partners who will be there to resource critical future opportunities, too. Building partnership around long-term effectiveness is critical.

For these reasons, I’d make the case that the top-right quadrant is actually the most sustainable. It puts nonprofit leaders in the driver’s seat on the path to impact, but also puts a learning mandate back on funders. Ultimately, this fosters partnership. And there are many who are incorporating robust learning in the definition of what “good” trust-based philanthropy looks like.

In Pursuit of Scalable Trust-Based Partnership and Proximity: Agency

It needs to be noted, trust-based grantmaking done well is not easy. Listening, learning, and acting in partnership requires thoughtfulness, good relationships, and attention. That requires time. Done poorly, it puts time overhead on nonprofit leaders, too. A single grantmaker can’t build close partnerships with 20 organizations, nor can a nonprofit leader have 20 funders requiring their time to “learn.” How, then, do funders achieve proximity at scale without putting time and attention burdens back on the organization?

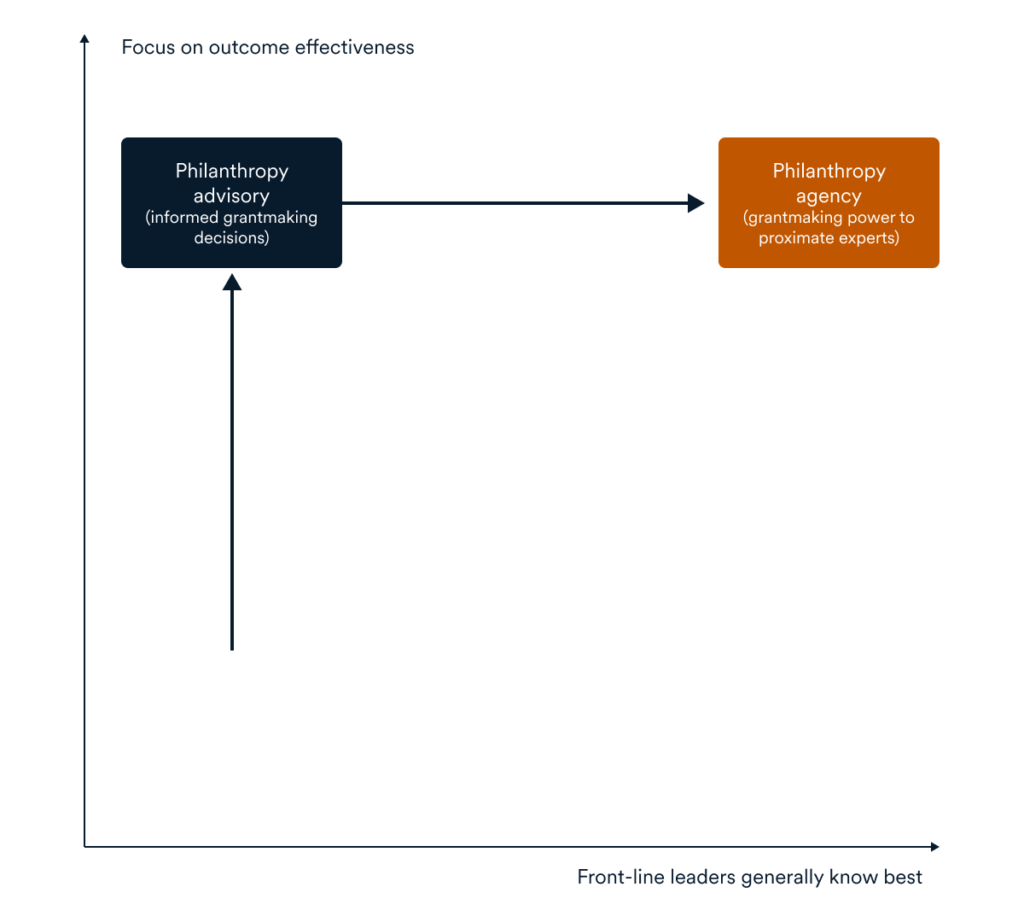

Philanthropy advisors can help funders move up the Y axis on the chart with greater scale, but a new model is needed to help funders increase their proximity without burdening nonprofit leaders.

“Philanthropic agency” can do this.

Akin to donor collaboratives, philanthropic agency calls for funders to relinquish their grantmaking rights and place trust in someone (an agent or agents) who has an impact-oriented mind and is partnered with organizations “on the ground.”

Moving to philanthropic agency can take various forms:

- Donor collaboratives with the decision-makers as proximate experts/leaders

- Setting up sub-funds and giving grantmaking authority to proximate leaders/experts

- Giving money to another funder who has more proximate partnerships in place

Perhaps a crude comparison, but information asymmetry and relationship costs are why venture capital exists in the for-profit funding landscape. Relationships, understanding, and partnership are needed at a fairly granular level to make high-quality investment decisions. Investors place “general partners” (agents) in charge of making all these decisions because they are more proximate to particular industries and issues and have time to build deeper relationships. They hold them accountable to performance and ethics, but these agents have full agency in deploying resources.

Philanthropic agency is similar. It empowers an agent with full decision-making authority and a mandate to build close relationships with partners in order to deeply understand their long-term needs and become a responsive, trusted, and dynamic partner.

The Dawn of Philanthropic Agency at Scale

Flavors of agency in philanthropy have been around for a long time. Foundations hire program managers who may have limited agency, The United Way aggregates donor money and grants on behalf of the community, and organizations like GiveWell select top-performing charities on behalf of their donors.

But until now, agency has been held back because of the expense of setting up these funding structures and the complications of maintaining trust.

That’s changing. In the coming years, the flexibility of donor-advised funds and technology are creating opportunities for funders large and small, personal and institutional, to create pools of charitable money in tax-deductible funds and name anyone as a co-grantmaker on the fund. At Charityvest, we’ve launched Community Funds, which can be hosted on public or private weblinks where the track record of the fund is completely transparent to anyone who has access.

We believe that philanthropic agency has the potential to solve the effectiveness and trust tension felt in the philanthropic world right now in a scalable way, increase equity through proximate decision makers, and increase the velocity of giving out of DAFs and private foundations, as funders may feel it easier to place their money in the hands of an agent faster than giving to individual organizations. Most importantly, it has the potential to increase the fun of giving as agents bring stories, foster relationships, and report on impact back to funders at a rate and scale they could not on their own.

What hangs in the balance is a more flourishing world.

Stephen Kump is co-founder and CEO of Charityvest. Find him on LinkedIn and follow him on Twitter.