This post is the third in “Social Justice and a Relevant Philanthropic Sector,” a five-part series by Miles Wilson about where philanthropy is stuck in old paradigms — and where there lie opportunities to advance social justice both within the sector and across American society.

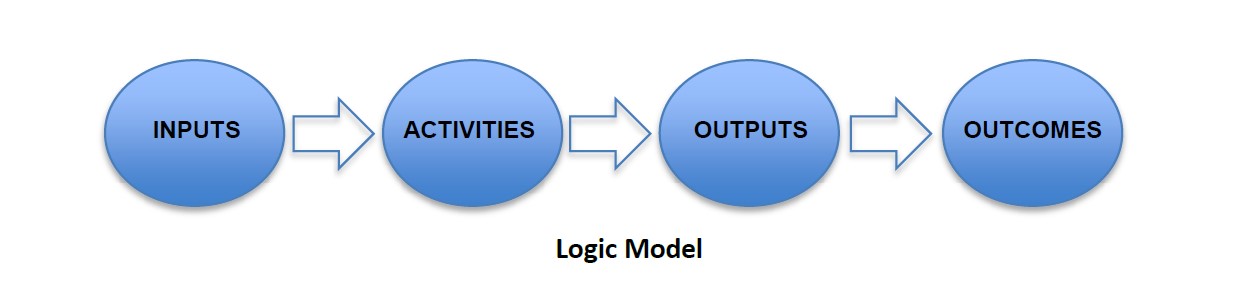

It’s been nearly 30 years since I first learned about the logic model approach to evaluation and saw how quickly it was permeating government, nonprofit, and business organizations and programs. At first glance, the logic model appears to offer a visual and simple way to think about moving through specific envisioned steps of an effort from concept to outcome.

Today, logic models are broadly insisted upon by foundations large and small, cutting across nearly all types of programs and initiatives. Despite their widespread use, however, there are real limitations and challenges with how logic models are being used, and philanthropy would be best served moving away from a “one-size-fits-all” approach to evaluation that prioritizes them.

Today, logic models are broadly insisted upon by foundations large and small, cutting across nearly all types of programs and initiatives. Despite their widespread use, however, there are real limitations and challenges with how logic models are being used, and philanthropy would be best served moving away from a “one-size-fits-all” approach to evaluation that prioritizes them.

One issue is that logic models are very linear and begin with “inputs” to lead to specific “outcomes.” Interestingly, this approach is not particularly logical as it asks one to use the means to show how one achieves a particular outcome, when in reality the outcome sought should drive the means — in other words, “form follows function.”

Logic models work best in simplicity but become rapidly confusing when complexity increases and there is need for flexibility and responsiveness to changing circumstances. This is particularly true for grant-supported organizations working in communities and populations in which poverty, unemployment, social disenfranchisement, and other challenging issues are merely presenting issues. The more fundamental or underlying issues are often overlapping and do not lend themselves to clear linear “if-then”-type statements.

Fortunately, there are other evaluation approaches out there besides logic models. Among the most promising is developmental evaluation, which is particularly appropriate for social innovation and systems-change initiatives. As evaluation expert Dr. Michael Quinn Patton writes in his book on the subject, “Traditional evaluation aims to control and predict, to bring order to chaos. Developmental evaluation accepts such turbulence and the way the world of social innovation unfolds in the face of complexity. Developmental evaluation adapts to the realities of complex nonlinear dynamics rather than trying to impose order and certainty on a disorderly and uncertain world.” Another approach is adaptive evaluation, which also recognizes the complexity of real-life circumstances and operating across contexts and populations.

What I currently find most exciting, though, is the increased promotion and use (albeit small at this point) of goal-free evaluation, an approach that pushes back on the constant focus on measuring impact on predetermined sets of goals. Goal-free evaluation allows organizations to respond to the broad programmatic interests of a funder to conduct its long-term work. At the same time, as Brandon Youker and Allyssa Ingraham write in a 2014 article in Foundation Review, an external evaluator, independent of both the nonprofit and the funder, “attempts to observe and measure all actual outcomes, effects, or impacts, intended or unintended, all without being cued to the program’s intentions.” It’s an unbiased view with a wealth of information regarding what is actually happening and where the greatest value appears to lie.

In their Stanford Social Innovation Review article, “Ten Reasons Not to Measure Impact and What to Do Instead,” authors Mary Kay Gugerty and Dean Karlan offer a clear caution about the focus on impact measurement:

“The push for more and more impact measurement can not only lead to poor studies and wasted money, but also distract and take resources from collecting data that can actually help improve the performance of an effort…To create a right-fit evidence system, we need to consider not only when to measure impact, but when not to measure impact.

Again, this pushes back against a foundation’s orientation to grantees and the often self-imposed pressure on them to demonstrate impact in nearly all circumstances. But the potential value provides opportunities for learning on both sides and a much deeper and more objective understanding of how and why programs might succeed or fail.

While goal-free evaluation is not intended to be a standalone evaluation, it holds great promise for becoming standalone with greater experience of use, and when paired with appropriate interim grant reporting. I also think that this form of evaluation is an excellent fit for the learning and accountability needs of funders that provide their grantees with long-term general operating support.

If done properly, evaluation also holds the potential to be a valuable tool for advancing diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in individual foundations and throughout the work of the field. ![]() Indeed, if DEI is to mean anything, evaluation must become fully incorporated into everything that happens in the work of philanthropy.

Indeed, if DEI is to mean anything, evaluation must become fully incorporated into everything that happens in the work of philanthropy. ![]()

Toward this goal, there is a wonderfully promising effort called the Equitable Evaluation Initiative, a five-year effort that attempts “to align evaluation practices with an equity approach — and even more powerfully, to use evaluation as a tool for advancing equity.” The Initiative’s approach is based upon four important principles: diversity of teams, cultural appropriateness, use of evaluation to reveal structural inequity, and advancing the community role in shaping evaluation. It is establishing critical infrastructure for embedding and assessing DEI efforts throughout the field and should be supported and embraced by foundations and field infrastructure organizations alike.

Philanthropy needs to recognize that organization size and access to resources should impact considerations of the type of evaluation deployed. In particular, small nonprofits and those operating in poorer regions and communities of color in literally every state are often negatively impacted by broad, one-size-fits-all approaches to evaluation. ![]() (Of the nation’s estimated 1.5 million nonprofit organizations, 72 percent have budgets of $500,000 or less, and of those, 61 percent have budgets of $100,000 or less, according to Nonprofit Finance Fund.)

(Of the nation’s estimated 1.5 million nonprofit organizations, 72 percent have budgets of $500,000 or less, and of those, 61 percent have budgets of $100,000 or less, according to Nonprofit Finance Fund.)

At the end of the day, the sector must recognize that a one-size-fits-all approach to evaluation doesn’t benefit foundations, nonprofits, or the constituents nonprofits seek to serve. ![]()

Miles Wilson is a philanthropic professional with nearly 30 years of experience supporting the U.S. social sector as well as past efforts in Northern Ireland, the Netherlands, and South Africa. He currently serves as deputy director of education grantmaking at Ascendium Education Group and wrote this piece while serving as a senior fellow during 2019 with the Aspen Institute Forum for Community Solutions.