It is one of the ideas with the greatest currency in philanthropy right now: More funders need to make large, unrestricted grants, and then trust nonprofits to use them well. Despite all the dialogue, however, the practice is still all too rare. Giving in this way still feels “risky” to many donors.

What actually happens when nonprofits receive large, unrestricted grants? The Center for Effective Philanthropy’s (CEP) recent examination of MacKenzie Scott grantees, along with complementary research by Panorama Global, sheds light on this question. (In the interest of transparency, it is worth noting Bridgespan is among Ms. Scott’s advisors, but was not involved in either CEP or Panorama’s research efforts.) The emerging empirical answer, per CEP’s report — is that “the effects have been dramatically and profoundly positive.” This creates grounds for optimism that giving in this way has breakthrough potential.

These are early observations, given the recency of the grants, the studies’ authors rightly note. Many wonder if a “lottery curse” akin to jackpot winners entering into “periods of wild spending” (as IDinsight’s Ruth Levine framed it) might manifest over time. To begin to flesh out that longer-term picture, we’d like to add another dataset to this growing body of insights.

Five years in, the story holds

In 2017, Ballmer Group made large, unrestricted grants to 21 U.S. nonprofits working to advance economic mobility. At the time, Ballmer Group was two years old and exploring ways to help organizations rapidly scale. Compared to the Scott sample CEP studied, Ballmer Group grants were similar in that they were large relative to the grantees’ size, lacked donor restrictions, and were a surprise to the grantees.

There were also some differences. Ballmer Group grantees’ median pre-grant budget ($21 million) was more than twice as big. The grants were disbursed evenly over five years (versus offered all up front for Scott grantees). And, at the time of the initial five-year commitment, grantees were told there was a possibility of renewal (Ballmer Group recently wrote about many of these renewals and lists all of their grants on their website).

Earlier this year, we interviewed leaders from 18 of these Ballmer Group grantees and studied public data for all 21 to understand their experience over the initial five-year grant period. Ballmer Group neither funded the research nor endorsed the findings. (In transparency, Bridgespan advised Ballmer Group on their sourcing and diligence for the initial grants and over time has provided independent strategic support to a handful of the grantees.)

Our findings were strikingly similar to CEP’s. By and large, the challenges donors often hypothesize that large, unrestricted grants will create — such as leadership team overload, internal culture tensions, strain in relationships with peer organizations, and hampered ability to fundraise — did not materialize. Instead, we heard that the funds created space for leaders to lead, built morale within the organization, allowed for re-granting or other forms of collaboration across the broader field, and served as a “vote of confidence” in conversations with other donors. Leaders were almost unequivocally positive about their grant experience.

Three clear signals

Common patterns in the organizations’ experiences elevate some important themes — both about what large, unrestricted grants can enable and, on the flip side, about the limitations of prevailing grantmaking practices.

1. Organizations invested in building their foundations as well as their programs.

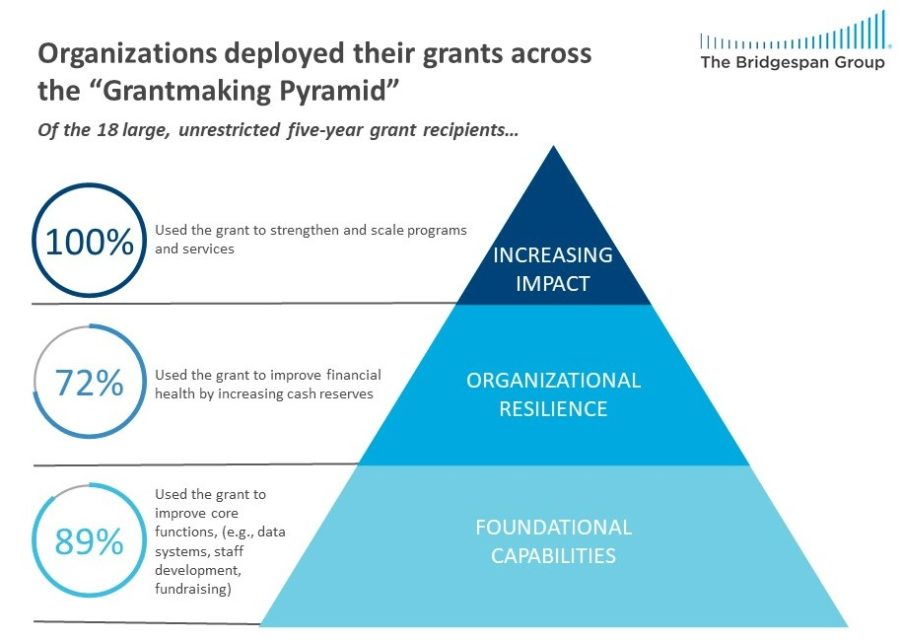

Ballmer Group grantees invested not only in growing their programs, but also in strengthening their organizations. All reported using the funds to increase impact directly, most often by providing growth capital for expansion, innovating on their model (particularly around digital delivery), or adding frontline staff. Nearly 90 percent also used funds to shore up foundational capabilities, such as measurement and learning, IT systems, and fundraising. Over 70 percent reported investing in organizational resilience, as reflected in their average cash reserves, which increased from about 3.5 months in 2017 to 6.5 months in 2021. In short, they leaned into all three levels of the “Grantmaking Pyramid” popularized by the Ford Foundation (see graphic).

Source: Framework by the Ford Foundation and The Bridgespan Group (see Time to Reboot Grantmaking); Bridgespan research of 18 recipients of large, unrestricted, five-year grants from the Ballmer Group.

The focus on strengthening core capabilities and building resilience was particularly striking. That so many leaders saw those investments as imperative provides further evidence that typical grant structures have starved these organizations. This pattern is particularly remarkable given the organizations’ size and maturity (most had been in operation for at least two decades). It echoes prior research on the prevalence of financial fragility, even among the most prominent nonprofit organizations in the sector.

As one leader described, “There was a recognition at the outset about the need for a stronger core to create a healthy organization capable of delivering the impact we’d set out to do. As a result of those investments in data systems, for example, we now have the ability to ask questions like, ‘Are children better off in our communities?’ and show the supporting analytics.” While the impact of these investments is not easy to measure in the short term, the leaders were adamant about their centrality to sustaining and scaling impact over time.

2. Leadership, not just the organizations, transformed.

Phil Buchanan, co-author of CEP’s study, shared in a recent webinar that while he wasn’t terribly surprised by the organizational benefits of the Scott grants, he “underestimated the emotional power for leaders.” We observed a similar dynamic for Ballmer Group grantees — even five years later. A piece of this that came through strongly in our interviews was the relief from the chronic fatigue of running an organization on a financial tightrope. This relief is especially important amid growing concerns about the widespread burnout of nonprofit leaders, particularly among leaders of color.

With more abundant resources, leaders adopted an abundance mindset. One leader shared how the grant “allowed me to shift the focus of my decision making. I was no longer operating in the fear zone. The investments we made in lots of small things that fall between the cracks had quite massive effects in terms of our organizational capacity and freeing my bandwidth to focus on the big things.” The leaders reported being able to shift their attention from defensive vigilance — staying constantly alert to the possibility that one bad fundraising month or one lost contract might cause a cash crunch that would require staff cuts — to readiness to consider and flexibly pursue opportunities for increasing impact.![]() As one CEO put it, “This was the first time I felt like I was actually the CEO running my organization — able to do what I thought was crucial for building the organization and increasing impact.”

As one CEO put it, “This was the first time I felt like I was actually the CEO running my organization — able to do what I thought was crucial for building the organization and increasing impact.”

And while these beneficial effects may very well have thwarted premature leadership departures, we also noticed patterns in healthy leadership turnover. Ten of the 21 organizations in our study experienced orderly, planned CEO transitions in the five-year grant period. Five of the outgoing 10 were founders, and the average tenure of the other transitioning leaders was nine years. This movement may have been experienced regardless of the grants, but most leaders (both new and former) acknowledged an interdependency: While the grants did not drive the decision, they contributed to all parties (former and new leaders, as well as boards) feeling confident that the new leader would inherit a stable organization with runway (in contrast to mounting evidence that, too often, this is not the case, especially for new leaders of color).

These leadership transitions also resulted in increased representation of people of color in the CEO role. Of the nine white outbound leaders, six were succeeded by leaders of color. This is particularly important given the critical assets leader of color bring to their roles.

3. Leaders imposed rigor.

The leaders felt the enormous responsibility of the opportunity and sought to be good stewards of the funds. Absent donor-applied restrictions, they recognized the importance of applying strategic rigor. Roughly half of the interviewed grantees used existing multiyear strategic plans or capital campaigns to guide their allocation decisions. Others (particularly those for whom large philanthropy was less common) spent significant time during the grant’s first year establishing decision roles for the funds, updating impact goals and strategic priorities, and identifying any under-resourced aspects of the organization that required investment to set them up for success. In the process, they made disciplined, intentional decisions.

Another strong signal in our interviews: Leaders’ belief that a clear strategy and proactive ownership of the narratives about the grant were critical to success. One leader reflected, “I remember thinking, ‘Oh my God, I’ve waited all these years to get a million dollars.’ We should go spend it. Then I thought, ‘Whoa, whoa, whoa.’ I learned then that it’s better to go slow and to be thoughtful and to put time and energy into thinking about how to use the resources.” The most common piece of advice they offered other recipients was not to rush to spend, but rather to pause and get a plan in place. “My concern would be making sure that leadership teams have the runway to plan before they need to get dollars out the door,” one grantee advised.

Beyond dispelling the lottery curse

Five years out, we did not see signs of a “lottery curse.” The nonprofits we studied did not buckle under the weight of large, unrestricted grants. To the contrary, they strengthened their organizations and leadership ranks, and they stewarded the funds with strategic rigor. They were able to innovate, adjust flexibly to new circumstances, and pursue new and more effective paths to scaling impact.

Will this be the evidence donors need to fundamentally reframe what constitutes “risky?” Will donors increasingly see that the real risk is not embracing this approach to grantmaking as a part of their portfolio? We’re hopeful that will be the case. And we are excited to continue as a fellow traveler with CEP, Panorama Global, and others as we collectively work to advance the knowledge base on this important topic.

Kathleen Fleming is a partner in The Bridgespan Group’s San Francisco office.

Anthony Michael Abril, a Bridgespan alum, is currently a Master of Public Policy candidate at the Harvard Kennedy School.

Jeff Bradach is the co-founder and former managing partner of Bridgespan.

The authors thank the nonprofit leaders who participated in this study for generously sharing their time and insights. They also thank their Bridgespan colleagues Kenichi Nozaki and Chuhan Shen (alum) for their contributions to the research, and Gail Perreault for her editorial support.