This is the fifth post in “Complicating the Narrative on Bridging and Division,” a six-part blog series from CEP and PACE (Philanthropy for Active Civic Engagement). This series seeks to highlight community-informed perspectives from five leaders in the build-up to the second event in CEP’s 20th Anniversary Virtual Learning Sessions: “Are We Better Off Divided? Philanthropy’s Role in Moving America Forward.”

The national tragedy surrounding the January 6 breach of the U.S. Capitol and its aftermath demonstrated the destructive potential of polarization in America. It has evolved into a singularly virulent and dangerous phenomenon.

Three months before the U.S. Capitol incursion, researchers from Northwestern, Harvard, Stanford, MIT, and seven additional universities documented how America’s polarized tribalism has metastasized into “political sectarianism,” an even more virulent phenomenon sharing attributes with religious sectarianism. The characteristics of political sectarianism are othering (seeing opponents as alien), aversion (deeply distrusting and disliking the other), and moralization (the attribution of wickedness and even criminality to the other).

Political sectarianism, the researchers write, leads to people “vastly overestimating” their differences with others. In a conflict we’ve moralized, for example, we experience opponents to be “more socially distant, ideologically extreme, politically engaged, contemptuous, and uncooperative than is actually the case.”

Thinking that polarization is “as bad as it can get” constitutes a failure of imagination. America is likely only at the beginning of this journey; absent intervention, we’re headed toward national violence and tragedy. Acting quickly and decisively, however, funders can help to prevent that from happening.

Polarization May Affect Funders, Too

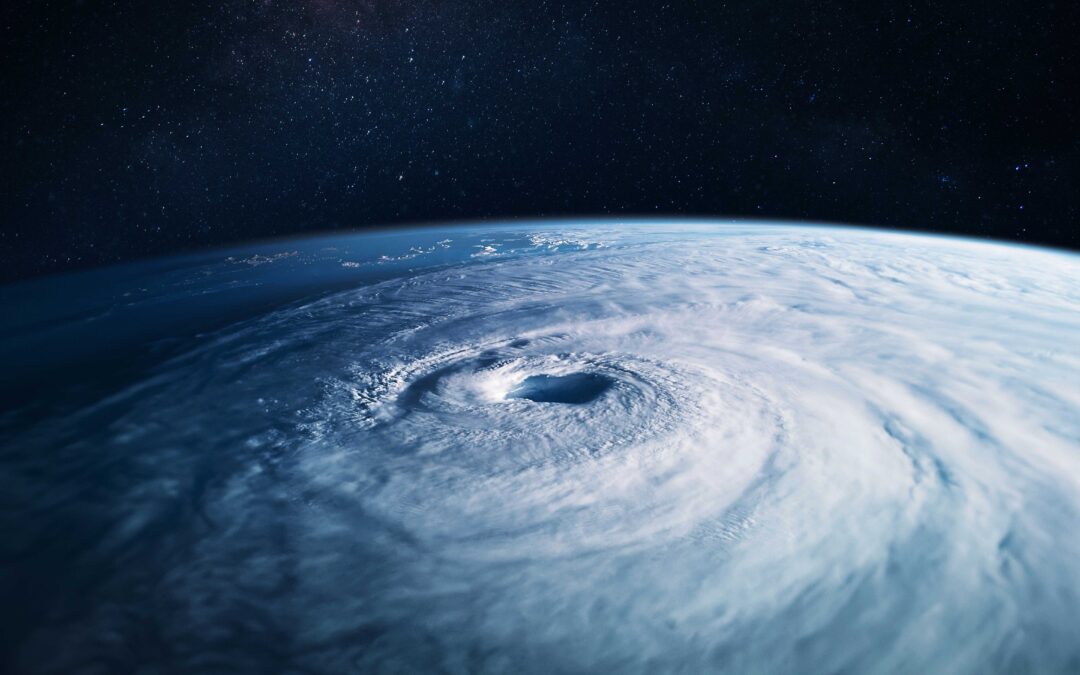

Bridging practitioners like myself are not surprised when national security leaders cite “domestic division as our greatest national security vulnerability.” As we joined in growing “bucket brigades” to douse the conflagration, many of us assumed that, post-election, resources and energy would begin flowing to counter America’s toxic divisions in proportion to the growing “wave” of awareness about the seriousness of the problem.

But we’ve been perplexed at receiving messages that are more mixed. “Wow, what you’re doing couldn’t be more urgent, timely, or hopeful” are words we hear every day. Yet, civil society’s response since November has felt more muted, infused by a sense of hesitancy and ambivalence about interventions bridging Americans across the divides.

It’s a good moment to ask several probing questions: Are we bumping up against practical limitations or exhaustion from addressing too many crises in the past year? Are we experiencing disbelief or denial that polarization can worsen and become more damaging beyond the election?

And, one particularly head-spinning query: How much is political sectarianism insinuating itself into the philanthropic and nonprofit communities’ approach to the polarization challenge? ![]() Or, to sharpen the point, might a growing perception that one side of America’s political divide is “morally bankrupt” be triggering skepticism about bringing the sides together?

Or, to sharpen the point, might a growing perception that one side of America’s political divide is “morally bankrupt” be triggering skepticism about bringing the sides together?

Considering, as Claudia Cummings emphasized in this series, that we are all breathing the air of toxic polarization, here are five considerations that funders might include in thinking through their role in moving America forward:

1. Primum non nocere — “First, do no harm.”

America’s civil sector has mostly internalized the “no harm” imperative in many contexts. Among philanthropists, it is part-and-parcel to acknowledging and establishing guardrails against unintended consequences of the power imbalance between funders and practitioners. Those working to heal civil society will usefully extend this internal work to understand and correct for the ways in which our institutions are influenced by the inevitable tug of political sectarianism.

In their contributions to this series, Kristen Cambell and Wendy Feliz warn about a particular kind of harm driven by making overly simplistic binary or zero-sum choices. Their insights call us to consider avoiding binary choices — which can mirror the polarized instinct to pick sides — in three contexts related to polarization:

- First, can we allow opposing racial injustice or supporting bridging work to become a zero-sum choice? These agendas foster difficult tensions (including plenty of chicken-and-egg dynamics), but complex reality dictates that each depends on the other to succeed. That is, bridging work — reducing enmity and building trust in each other and in institutional integrity — cannot succeed while we fail to address our legacy of racial injustice.

Neither will racial inclusion and equity work fully succeed if driven solely by one party in our polarized environment, and without taking into account a broad range of views that buy into shared goals.

Neither will racial inclusion and equity work fully succeed if driven solely by one party in our polarized environment, and without taking into account a broad range of views that buy into shared goals. - Likewise, we could err in deciding that either democratic structural reform or bridging work offers the solution. Don’t we need both? Effective reforms will support a future that is healthy and pluralistic and will interrupt what Andy Hanauer calls the “Polarization Industrial Complex.” However, it is bridging — bringing people together face-to-face — that will help drive the cultural and normative changes we seek.

- Finally, although effective bridging organizations are neutral, funders should be able to support specific solutions and, at the same time, support bringing together people on all sides of the issues to understand each other. A corollary: we can despise a particular political figure without directing that antipathy toward their mainstream, grassroots supporters.

2. Act with urgency — even outside of traditional lanes.

Market forces will hopefully lead many non-bridging institutions to join the all-hands-on-deck bridging work across large audiences. Companies, colleges and universities, social organizations, and religious communities (to name a few) can meet Americans where they are and support their employees, students, members, customers, and neighbors in overcoming perilous divides.

Funders with the requisite capacity and flexibility might consider whether meeting the urgency and high stakes of combatting toxic polarization allows — as other crises have in the past year — short-term reallocations or relaxation of often-unforgiving lines demarcating foundation priorities and practices.

Thousands of practitioners in hundreds of bridging organizations have stepped up the urgency with which we expand our work, and we are generating ever more exuberant and astonished reactions from participants rethinking their powerful, but misplaced, certainty in each other’s moral decrepitude.

It’s self-evident that practitioners’ urgent action is unsustainable if the funding community is unable to act with the same urgency.

3. Help strengthen the collective impact of the bridging field.

Together, the bridging field is responding to the call for Americans to listen to each other through evidence-based programming. Organizations are coalescing to augment that call, fulfill demand, and invite collaborative dialogue across our divides. We are also working to build a collective national voice and to grow our field without falling into zero-sum contests with each other for scarce resources.

Organizations in the bridging field all share one key aspect of our work: bringing people together across differences to find common ground. Yet, far from monolithic, the field includes organizations engaging different audiences, leveraging different physical and digital approaches to engagement, and — most important — targeting different outcomes.

For example, different organizations:

- Convene divided leaders and interests to develop solutions to national policy challenges;

- Engage diverse participants to address urgent local issues (e.g., hunger, homelessness, opioid addiction, community/police conflict, etc.);

- Equip religious leaders to engage their congregations in anti-violence work;

- Support Members of Congress to increase cross-party collaboration;

- Engage college students in bringing diverse peers together around political issues;

- Build evidence of grassroots majorities supporting solutions to national problems; and

- Bring individuals with divergent views together to strengthen local social cohesion.

These are just a few examples of the many ways in which bridging organizations work. We aim to strengthen our collective ability to meet the challenge before us with sufficient reach, quality, diversity, and alacrity to move the needle — and, we aim to understand the right way to align this work, individually and as a field, to attract expanded resources. This includes finding opportunities for the field to be in sustained dialogue with the philanthropic community.

4. Consider collaborative dialogue to foster solutions to issues.

Funders unable to provide direct support for bridging work might also consider leveraging collaborative dialogue to address priority issues already within their portfolios.

Seemingly intractable issues become unstuck when competing interests look together for solutions that can be widely supported (and are sustainable across party leadership transitions). Moreover, dialogue across opposing political, ideological, and sectoral interests is essential to innovating solutions for America’s layered crises right now: ending the pandemic; sending people back to work; getting students back to school; addressing generational and racial injustice; and making progress on many other implicated issues like mental health, gun violence, immigration, healthcare, and digital disinformation, to name a few. ![]()

5. Whether you fund bridging work or not, participate in bridging activities.

Swimming in a toxic-polarization stew, even the most politically seasoned and self-aware among us often still “can’t fathom” certain others’ beliefs, positions, and votes. Participation in effective bridging programs helps all of us better understand those with opposing perspectives, as well as our own internalization of polarization.

To that end, two upcoming national bridging initiatives, hosted collectively by the hundreds of bridging organizations that make up the field, offer funders a chance to engage along with many tens of thousands of other Americans: America Talks, June 12-13, 2021 and the National Week of Conversation, June 14-20, 2021. Funders can also learn more about bridging work in a philanthropy-specific context in CEP’s event later this month, “Are We Better Off Divided? Philanthropy’s Role in Moving America Forward.”

It’s Time to Make Urgent Choices and Take Action

Majorities of Americans on all sides view those who believe and vote differently than they do as threats to America — and as immoral, malevolent, and contemptuous destroyers of sacred values. Polarization’s radicalization invites terrible near-term consequences, and funders working to heal our democracy are not immune to its moralistic pull. ![]() This fire-lit moment calls for funders to take good, hard looks at the challenge, at themselves, and at America’s alternatives — before answering whether and how they might join the bucket-brigade to put out the flames.

This fire-lit moment calls for funders to take good, hard looks at the challenge, at themselves, and at America’s alternatives — before answering whether and how they might join the bucket-brigade to put out the flames.

The following call to action in a recent email I received from one bridging organization resonates, for me, with the moment:

Are you ready to bridge?

Ask yourself, deeply and honestly:

What is the alternative?

David Eisner is president and CEO of Convergence Center for Policy Resolution. Follow Convergence on Twitter at @ConvergenceCtr.We are interested in diversifying perspectives and democratizing this conversation. If you would like to share your thoughts on the questions we’re posing to respondents in this series, please do so here.